The Courage to Create

My thoughts on a gem of a book that deserves a spot on every creative’s bookshelf. 📚

When people hear I study creativity, one of the most common questions I get is: “What book should I read [about creativity]?” It’s a question that’s deeply individual and entirely dependent on what one is hoping to find. Some people want practical techniques, others philosophical debate. Some are intrigued by scientific research and others simply need an inspiring friend along the journey.

It is with this motivation that I’ll be doing a series over time of the most impactful books on creativity I’ve read across a wide variety of thinkers, creators, and scientists. I’ll be creating a dedicated page where you can find all of these recommendations in one place as the collection grows. Consider this the beginning of a living resource we’ll build together. 📚✨

This book is very near and dear to me. It inspires, it gives perspective, and, most importantly, it gave voice and clarity to my deeply felt beliefs about creativity that I had never heard articulated in such a way before. Rollo May’s “The Courage to Create” is a book that I’ve quite literally underlined and/or tabbed almost every page.

To back up, Rollo May was a theologian-turned-psychologist who helped found existential and humanistic psychology in the 1950s–80s. His work focused on human suffering and our search for meaning, exploring everything from anxiety and free will to love and creativity. When I first came across The Courage to Create, I was immediately intrigued, but I wasn’t sure what to expect from a fifty-year-old book.

Its opening line states, “we are living at a time when one age is dying and the new age is not yet born.” A sentence that feels strikingly appropriate in this moment. May suggests that we have a choice in what this new age is. We can either “withdraw in anxiety and panic… as we feel our foundations shaking” or we can “seize the courage necessary to preserve our sensitivity, awareness, and responsibility in the face of radical change.” We can “consciously participate, on however small the scale, in forming of [this] new society” and we can choose to make our own creative contribution by embracing the courage that it takes to live a creative life.

REDEFINING CREATIVITY

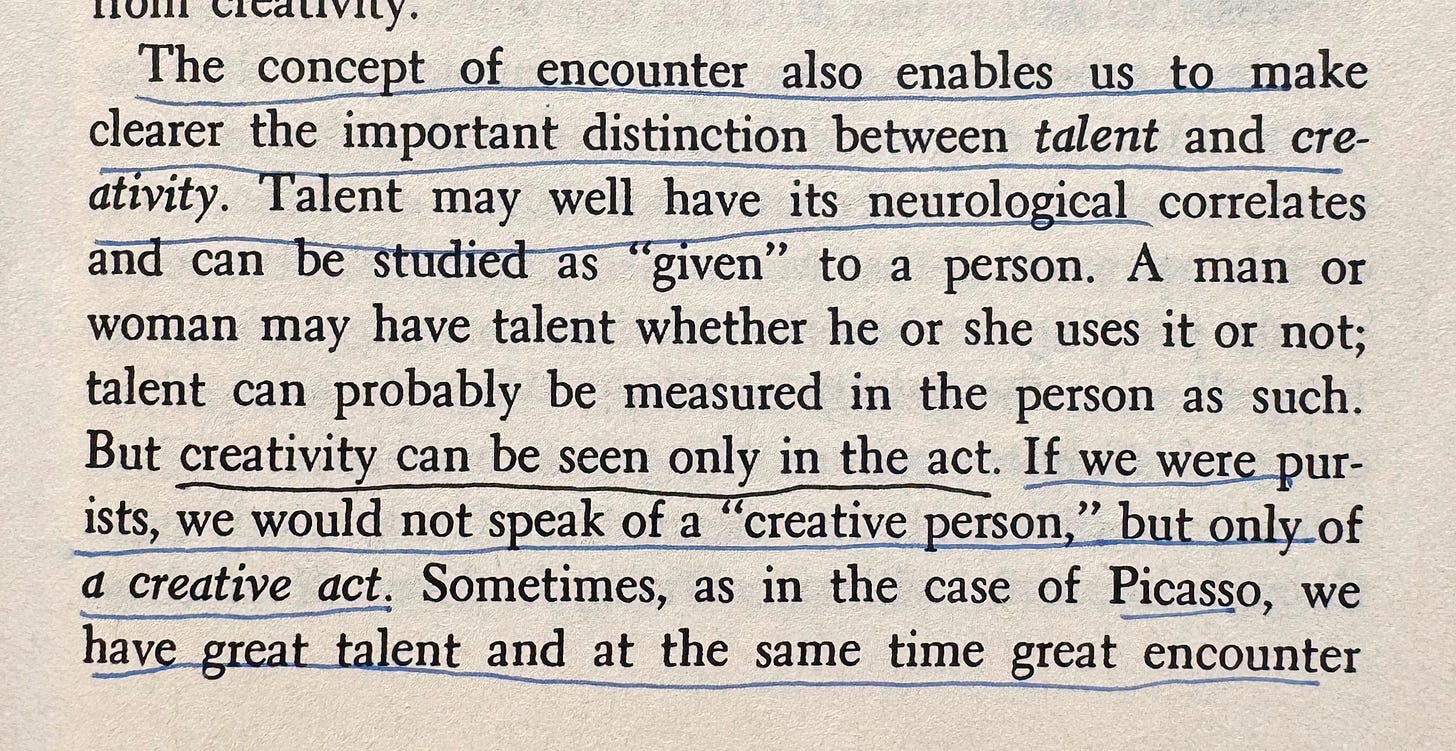

May believes (as do I) that creativity is so much more than painting or music or possessing artistic talent. It’s a way of being and approaching and changing the world. But what does this actually mean?

May defines creativity as “the process of bringing something new into being.” He places particular emphasis on the need to distinguish between “pseudo forms” of creativity that he sees as “superficial aestheticism.” While “art as artificiality” serves a purpose, it does not provide the same level of impactful action as the creativity we are discussing here. He believes true artists expand how we see and understand the world. At the same time, creativity is also deeply personal—“the most basic manifestation of a man or woman fulfilling his or her own being in the world.”

Rising to one’s full potential, what humanistic psychologists often refer to as self-actualizing, is possible through creativity. This idea stands in stark contrast to the all-too-common messaging that, as creatives, we must suffer for our gifts. May strongly disagrees with his predecessors (Freud) and mentors (Alfred Adler), who had less than positive interpretations of creative individuals. Instead, May strongly believes we must reject the harmful idea that “talent is a disease and creativity is a neurosis.” This was quite an uncommon perspective in psychology at the time.

Even if we aren’t ruled by the thoughts of Freud and Adler today, these messages still run deep. I’m constantly asked about “the tortured artist” concerning my research on creativity and well-being in creative individuals. More insidiously, I recall this messaging being reinforced throughout my time in art school... That extreme amounts of suffering just comes with the territory of being an artist or designer. That if you were feeling the pain, you were on the right track, and that any suggestion for relief might remove your edge or dampen your creative abilities. May’s humanistic perspective stands strongly in opposition to these harmful notions with a refreshing and inspiring message on creativity:

The creative process must be explored not as the product of sickness, but as representing the highest degree of emotional health, as the expression of normal people in the act of actualizing themselves. Creativity must be seen in the work of the scientist as well as in that of the artist, in the thinker as well as in the aesthetician; and one must not rule out the extent to which it is present in captains of modern technology as well as in a mother’s normal relationship with her child. Creativity, as Webster’s rightly indicates, is basically the process of making, of bringing into being.

So if creativity isn’t about suffering and it’s so much more than talent, what is the key ingredient? May believes the answer lies in what he calls the “encounter.” This encounter can be between one’s self and one’s environment or with one’s “inner vision.” Essentially, confronting and bringing your reality into hyperfocus in a process of intensely interrelating with your world. Practicing true presence.

Returning to the differentiation between superficial aestheticism and genuine creativity, only the latter requires this high degree of absorption and intensity of encounter and stands independent of talent. This courage of presence and heightened consciousness is what allows us to move beyond what has been holding us back and pushes us towards more fertile ground. While this can be difficult and at times sparking anxiety or fear, when we’re fully committed to the encounter, we are rewarded with the pure joy of experiencing the “actualizing one’s own potentialities.”

THE PRICE OF CREATIVE COURAGE

Now that we understand this more expansive definition of creativity, it becomes clear why creative people have always faced resistance. Throughout history, there has been suspicion of “artists, poets, and saints. For they are the ones who threaten the status quo, which each society is devoted to protecting.” May elaborates:

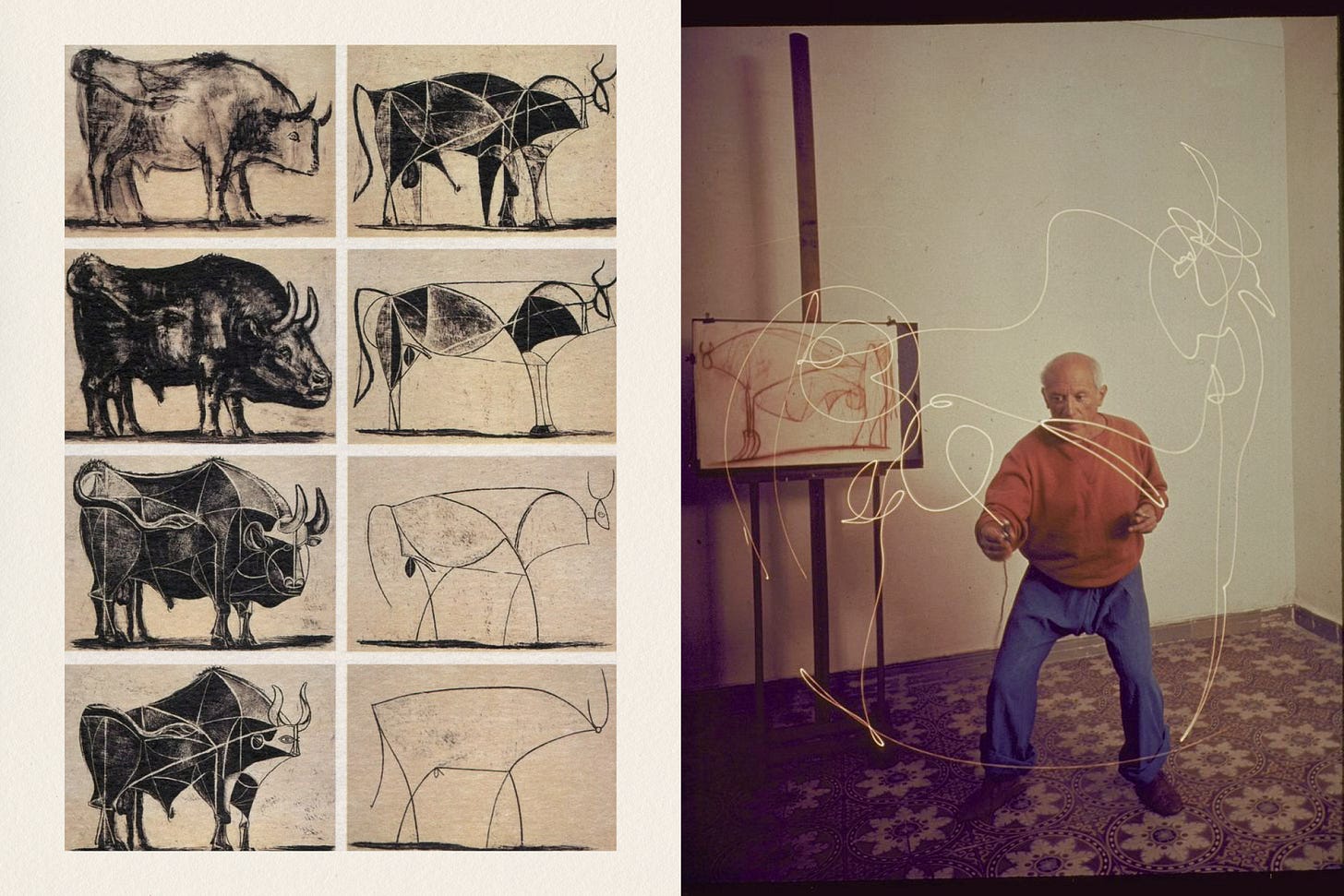

Whenever there is a breakthrough of a significant idea in science or a significant new form in art, the new idea will destroy what a lot of people believe is essential to the survival of their intellectual and spiritual world. As Picasso remarked, ‘Every act of creation is first of all an act of destruction.’

This may sound grandiose, but I’d be surprised if there’s a single creative person who hasn’t experienced judgment around their ideas, doubt about their career choices, or repercussions for pushing boundaries too far and upsetting the herd.

Despite these challenges, what sets creative people apart, according to May, is their willingness to live with anxiety and uncertainty, even when it costs them security and comfort. Rather than running from the unknown, they encounter and wrestle with it, forcing it to “produce being.” This courage goes beyond mere endurance and extends to voluntarily choosing disruption over comfort. May describes artists and creatives:

This required intensity or driving force, he calls “rage.” Not anger, but something deeper:

We could call this intensity by many different names: I choose to call it rage. Stanley Kunitz, contemporary poet, states that ‘the poet writes his poems out of his rage.’ This rage is necessary to ignite the poet’s passion, to call forth his abilities, to bring together in ecstasy his flamelike insights, that he may surpass himself in his poems. The rage is against injustice, of which there is certainly plenty in our society. But ultimately it is rage against the prototype of all injustice—death.

However difficult this work may be—structuring chaos, channeling passionate rage, facing possible rejection—May reassures us that history doesn’t favor those who cling to the status quo. Instead, he writes, “there is a profound joy in the realization that we are helping to form the structure of the new world. This is creative courage, however minor or fortuitous our creations may be.”

I appreciate how May consistently reminds us throughout the book that even our smallest creative acts matter. Despite using monumental historical figures to illustrate his points, he emphasizes that any creative contribution, no matter how modest, moves us in the right direction.

TECHNOLOGY & AUTHENTIC CREATION

I won’t spoil the whole book, but there are so many other fascinating topics covered. While rereading on holiday last week for the umpteenth time, a new passage spoke to me that I had glossed over previously. I think the relationship between creativity and AI is something on a lot of creatives’ minds these days. I was amazed to read May’s relevant warnings on the much more quaint (in retrospect) technologies of his time:

What I am saying is that the danger always exists that our technology will serve as a buffer between us and nature, a block between us and the deeper dimensions of our own experience. Tools and techniques ought to be an extension of consciousness, but they can just as easily be a protection from consciousness.

This tension feels especially acute today. Where May worried about television creating passive consumption, we now grapple with AI that can generate art, write prose, compose music, and even write personal statements for us. The question isn’t whether these tools are inherently good or bad, but whether we’re using them as extensions of our creative consciousness or as substitutes for the difficult, messy, essential work of genuine encounter with our world.

It is only by being in touch with our consciousness, even the irrational aspects, that we can have this “free, original creativity of the spirit.” To which May argues is not only the basis for poetry, music, and art, but also scientific creativity and societal progress.

Similarly, he spoke about the risks of the era of mass communication. Now in the age of social media, the risks are only exponential to what they were in the 1970s. He writes:

Mass communication… presents us with a serious danger, the danger of conformism, due to the fact that we all view the same things at the same time in all the cities of the country. This very fact throws considerable weight on the side of regularity and uniformity and against originality and freer creativity.

If May was concerned about the homogenizing effects of shared television programming, imagine what he would make of algorithmic feeds that serve us increasingly similar content based on engagement patterns. The creative courage and presence he advocates for becomes even more essential when our digital environments actively reward conformity and punish the kind of boundary-pushing originality that genuine creativity requires.

May’s vision of creativity as a way of being—rather than merely a way of making—offers us a framework for navigating our modern creative challenges. His insights feel especially vital now. Creativity isn’t about aesthetics or talent but about the courage to encounter reality fully. Our rage against conformity and death can fuel meaningful work, and that even our smallest creative acts help form the structure of a better future.

Perhaps most importantly, May reminds us that creativity isn’t the “frosting” on a well-lived life. Creativity is fundamental to human flourishing and self-actualization. In a time when we’re constantly told to optimize, hustle, and produce, his call to slow down and truly be present as we encounter our world is a reminder we so dearly need.

If this resonates with you, I cannot recommend The Courage to Create highly enough. At just 140 pages, it’s a book you can read in an afternoon but will find yourself returning to for years. Every time I open it, different passages speak to me, wherever I am in my creative journey.

With courage and curiosity,

Kaile

UP NEXT:

🧠 Field Notes #01 — Inside the Creative Brain

Dispatches from the Paris Brain Institute at The Sorbonne! What world-leading neuroscientists are discovering about creativity, translated into insights for your creative practice.See you then!